Download the PDF version of this report

Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Background on Residential Treatment

- Problems With Residential Treatment

- Recommendations: Use Data Effectively

- Recommendations: Prevent Unnecessary Institutionalization by Prioritizing High-Quality Community-Based Services

- Recommendations: Improve Quality of Residential Treatment

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- Endnotes

Executive Summary

Children and adolescents in Ohio who need mental health services often end up in residential treatment facilities, disconnected from their families and communities. These facilities are intended to provide short-term, intensive services to high-needs youth in order to identify and address the focal problem necessitating out-of-home care and return them to their homes and communities. But too often, youth are placed in residential facilities unnecessarily because they cannot access high-quality community-based services. At the same time, due to a lack of outcome data and evidence-based standards, it is difficult to determine whether youth benefit from residential treatment.

Because of our longstanding commitment to advocating for youth in residential treatment facilities, Disability Rights Ohio worked with national experts to review Ohio’s residential treatment system. We consulted with stakeholders, including youth and families, to assess Ohio’s system and identify areas for improvement. In this report, we note the barriers that currently exist in Ohio, and we make the following recommendations:

- Use data effectively to assess services and improve outcomes

- Use currently available data to assess outcomes

- Dedicate staff to analyze data and oversee quality improvement

- Make data, assessments, and other information available to the public

- Prevent unnecessary institutionalization by prioritizing high-quality community-based services

- Make a statewide, cross-agency commitment to eliminate unnecessary residential placements

- Incentivize diversion from residential placements through development of high-quality community-based services

- Perform a statewide needs assessment and develop a level of care tool for facility admissions

- Ensure that community-based services are adequately funded and available throughout the state

- Improve the quality of residential treatment

- Unify state standards and oversight in one cross-agency team

- Develop a rating system to incentivize and reimburse the adoption of outcome-based practices, including:

- Implementation of trauma-informed care to address youth trauma

- Elimination of restraint and seclusion, including chemical restraint

- Engagement of families and youth engagement in treatment and facility operation, including elimination of custody relinquishment

- Prioritization of discharge planning and community connection from the time of admission to promote transition back into the community

- Ensure health, safety, and rights of youth in residential treatment

- Prevent abuse and neglect through youth empowerment and mandated reporting of abuse and neglect by facility staff

- Establish a statewide ombudsman office to advocate for children in out-of-home care and assist in resolving complaints, similar to the Long-Term Care Ombudsman for adults

By taking these steps, Ohio can meet the needs of youth while preserving families, preventing further trauma, and ensuring that services are effective.

Introduction

As Ohio’s protection and advocacy system for people with disabilities, Disability Rights Ohio has a long history of monitoring residential treatment facilities for youth receiving mental health services.1 DRO has advocated for the rights of youth who are receiving treatment in out-of-home settings and has investigated reports of abuse and neglect in these facilities. This experience led DRO to complete a comprehensive review of Ohio’s residential treatment system. We worked with Dr. Janice LeBel and Beth Caldwell, national experts in residential treatment,2 and stakeholders throughout Ohio to gather information about Ohio’s system and compare it to national models and best practices.

We are publishing this report now because we hope to add to the state’s current conversation on how to best serve youth with mental health challenges and histories of trauma. In 2016, Ohio legislators began to examine the difficulties faced by children and adolescents who are involved with multiple service systems, including the mental health, developmental disability, juvenile justice, and children services systems. These young people, termed “multi-system youth,” face numerous challenges receiving the services they need and transitioning to adulthood. The Ohio Joint Legislative Task Force on Multi-System Youth recently issued a report with broad recommendations to ensure that these systems work together to meet the needs of youth and their families. Included in the task force’s report are recommendations that Ohio undertake a critical examination of congregate care facilities, and review the financing, appropriateness of care, and access to services at these facilities; this report is intended to complement those recommendations with concrete action steps and to provide context for the comprehensive review recommended by the committee.

This report addresses the steps that Ohio needs to take to ensure that young people receive the services they need in an appropriate setting, and that those services are high-quality and do not subject them to further harm. We recommend that Ohio use data effectively to assess and improve services, prevent unnecessary institutionalization by prioritizing high-quality community-based services, and improve the quality of residential treatment.

Background on Residential Treatment

High-quality residential treatment services are intended to be a last resort for youth whose conditions or behavior cannot be safely treated in a community setting, such as youth who start fires or those with sexually problematic behavior.3 Each youth has unique needs, and treatment options should be based on those individualized needs. Outcomes should be carefully measured and monitored to ensure that the services are meeting the needs of youth and leading to positive results.

Ohio currently licenses 23 Children’s Residential Centers and 11 Certified Group Homes which offer residential treatment services for youth.4 These Residential Treatment Facilities (RTFs) are not hospitals, and this report does not examine hospital services because hospitals serve a different purpose for youth with acute mental health needs. Past studies have estimated that 8% of children with mental health needs utilize RTF services.5 RTFs provide care and supervision twenty-four hours a day for two or more consecutive weeks. The types of services provided vary across RTFs and can include individual therapy, group therapy, medication management, recreation therapy, substance abuse treatment, and a variety of other services and supports. Stays are intended to be short-term and involve intense treatment with a goal of transitioning youth safely back to their homes and communities as soon as possible.6

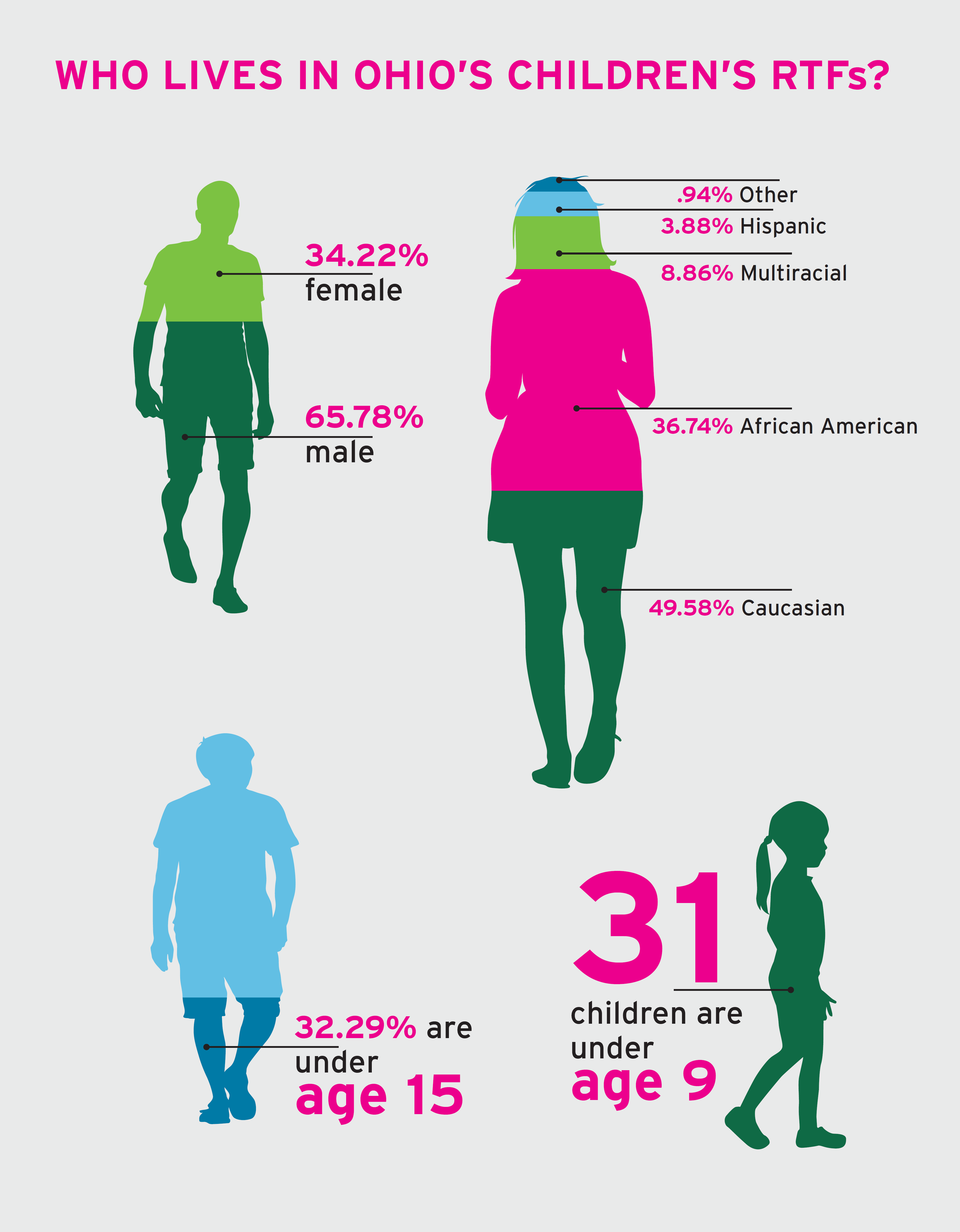

Although there is little publicly-available data about the youth in RTFs, a point-in-time analysis on July 31, 2016, noted over 1,900 youth in Ohio’s RTFs. These youth are disproportionately male and African American; over 65% of youth in RTFs were male, and over 35% were African American, while only 13.7% of Ohioans are African American. Nearly one-third (32%) were under age 15.7

These youth often have histories of sexual or physical abuse, domestic violence, community violence, or other trauma.8 They require care and support that is aware of the trauma they have experienced and provides them with the services and supports that assist them in developing the skills and tools needed to achieve positive outcomes.9

The youth in RTFs are involved in a complex set of systems. Due to restrictions on funding sources, payment for these services is often a patchwork of funds from the Ohio Department of Medicaid or other health insurance (for medical or mental health services), the local school board (for education services), and children services agencies (for room and board). The RTFs in which they reside may be regulated by the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services (ODJFS)10 or the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (OhioMHAS)11 —or both. Some youth are placed at these facilities through juvenile courts. Some may also receive services through county boards of developmental disabilities.

There are more effective and less costly evidence-based alternatives to residential treatment including Therapeutic Foster Care,12 intensive in-home therapy,13 multi-systemic therapy,14 and Functional Family Therapy.15 However, access to these services is limited, especially in Ohio’s Appalachian counties.16 Funding for other services that are designed to prevent residential placement, such as crisis stabilization17 and respite, remains extremely limited. There is also limited access to appropriate mental health and trauma treatment services for youth, leading to an increase in unnecessary RTF placements.18, 19

Ohio has taken steps to improve access to home and community-based services, including continued investment in programs such as the Strong Families Safe Communities Program, which provides grants to local communities for crisis intervention and care coordination services for youth with behavioral health needs or developmental disabilities that place them at risk of harm to themselves or others or risk out of home placement.20

Ohio’s Family and Children First Councils have also been effective in providing service coordination and other services and supports for families and children who are at risk of out of home placements. Of the families that were able to access service coordination services funded by Family and Children First Councils during 2015, 95.9% of children remained in their own homes.21 However, funding for these councils is limited, and levels of service vary widely across counties.

SIDENOTE

Trauma informed care (TIC) is a systems-focused framework for service delivery that acknowledges trauma in the lives of all persons – including consumers and providers. TIC identifies these events not as past experiences but as experiences that help shape a person’s core identity. Service delivery is structured around recognizing these experiences and minimizing retraumatization. The core principles are safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration, and empowerment.

SIDENOTE

Amy is 14 years old and is diagnosed with autism, disruptive behavior disorder, and intellectual disability. She requires 30-35 hours of in-home support per week. Currently, her parents are employed in order to meet the family’s needs. They have repeatedly asked for in-home staff to help Amy live at home. However, each agency they contact tells them that their agency is not designed as a long-term source of funding to help Amy live at home. There is no help for Amy unless her situation deteriorates to a point where she is at risk of losing her home.

(Source: Testimony to the Joint Legislative Committee on Multi-System Youth)

Problems With Residential Treatment

Because RTFs are institutional settings, there are several inherent problems that require careful consideration. Youth in RTFs are affected by the physical environment of the facilities, service provision requirements, and funding sources. Ohio must address the gaps in its current systems that increase the risks to youth in RTFs.

ODJFS and OhioMHAS set basic licensure standards for RTFs22 that cover topics such as staffing requirements, building maintenance, service plans, and complaint policies. However, there is no staff at OhioMHAS that are dedicated to overseeing RTFs, as these staff are also responsible for monitoring hospitals, adult care facilities, and other settings. While the facilities themselves are regulated by ODJFS and/or by OhioMHAS, the youth who reside there often receive services from multiple state systems. There is little communication about RTFs among these agencies, leading to confusion as to whose responsibility it is to handle concerns or which agency’s standards apply.

Of deep concern to advocates is that many families must relinquish custody of their child in order to access intensive mental health services. Private health insurance plans may cover outpatient treatment and acute hospital care, but not intensive community-based services and residential treatment services. Families who cannot afford to pay for such services either forgo needed care, or relinquish custody to the state so the child will become eligible for Medicaid and receive the treatments that they need. Custody relinquishment not only complicates the system of care by involving additional agencies, but also impairs treatment outcomes as families are no longer as involved in their child’s treatment.23 As a result, the Public Children Services Association of Ohio estimates that nearly one in three children entered into agency custody due to custody relinquishment.24

While youth receive treatment in residential facilities, they are also entitled to receive education services, including special education services if they are eligible. Facilities arrange for education services in different ways, including transporting youth to local schools or providing on-site education services through a contract with a local school district, educational service center, or charter school. Due to competing demands for time for education and treatment, youth often report receiving fewer educational hours than state law requires for general education students or than a student’s Individualized Education Program requires. This diminishes the chances of youth being able to keep up in school.

For youth who are aging out of the child-serving systems, there is little planning for post-secondary education or employment opportunities. Many youth are eligible to receive services through Opportunities for Ohioans with Disabilities to assist with transition to post-secondary education or to find and retain employment, but RTFs do not systematically connect youth to these programs. OhioMHAS has several initiatives to support transition-aged youth, but more must be done to ensure that youth in RTFs can benefit from these programs.

While widely used, RTF placement is not only restrictive, but has been shown to be ineffective and potentially harmful for some youth.25 Youth in RTFs are vulnerable to abuse and neglect, including well-documented cases of sexual abuse and restraint-related death.26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 From October 1, 2014, through September 30, 2015, facilities licensed by OhioMHAS reported 807 major unusual incidents including physical abuse, sexual abuse, assault, serious injurious behavior, and injuries due to restraint or seclusion. The number of major unusual incidents is estimated to be under-representative of actual incidents of abuse, and these totals do not include facilities or units licensed by ODJFS. Additionally, research demonstrates that youth may develop inappropriate or anti-social behaviors when they are exposed to the behavior of other youth in the facility.32 Youth may make gains between admission and discharge, but not maintain this improvement once they return to their communities, creating a cycle of readmission to RTFs or even juvenile justice facilities.33

SIDENOTE

Disability Rights Ohio investigated a facility in Southern Ohio after receiving notification of potential unapproved use of restraint. DRO discovered multiple health and safety violations, including broken windows, holes in the floor, and bathrooms with what appeared to be mold covering the walls. The facility needed over $500,000 in repairs to be in compliance with standards.

(Source: DRO Investigation)

SIDENOTE

A facility in Western Ohio was found to seclude youth by allowing staff members to sit in a chair placed in front of a youth’s closed bedroom door – pressing their hands and feet on the door – to keep the youth from getting out. Staff members reported that they did not consider this practice to be seclusion. They believed that because there was a staff member sitting in the chair, the practice did not count as a seclusion.

(Source: Columbus Dispatch May 5, 2014)

Major Unusual Incidents Reported - October 1, 2014 through September 30, 2015Type of Incident |

Number |

|---|---|

| Physical Abuse | 334 |

| Verbal Abuse | 61 |

| Sexual Abuse | 10 |

| Neglect | 39 |

| Restraint and Seclusion Related Injury | 83 |

| Unapproved Use of Restraint or Seclusion | 32 |

| Assault | 73 |

| Serious Inurious Behavior or Suicide | 168 |

| Other Major Unusual Incidents | 7 |

| Total Major Unusual Incidents | 807 |

The process of reporting abuse and neglect is not trauma-informed, and youth who submit reports are often not provided with trauma-informed services. Most youth in RTFs have been previous victims of abuse or neglect34 and may not recognize acts of abuse or neglect as something to report. Youth who do recognize situations of abuse or neglect may fear retaliation. While OhioMHAS-licensed RTFs are required to have resident rights officers, often youth do not know who these individuals are or how to contact them. Resident rights officers may have other roles at the facility, and they frequently lack the training, support, resources and authority to address problems. At many facilities, information about rights or resident rights officers are not presented in a manner that is accessible to all youth, leaving many youth unaware of their ability to report abuse or neglect.

Additionally, many RTF staff are not mandated reporters and therefore are not legally obligated to report suspected incidents of abuse or neglect to children services. Unlike the developmental disability system, staff who are not professionally licensed (e.g., social workers, psychologists) are not mandated reporters of child abuse.35

While there are strong efforts to address the mental health care needs of Ohio youth, admissions to RTFs, including children under age 12, are increasing. Children continue to be placed in RTF programs that are not demonstrated to be as effective as home and community based services and placed at risk of harm because the evidence-based home and community based services that they require are simply not available in their communities.36 Ohio does not collect data or track outcomes for youth in RTFs, making it impossible to determine if RTFs are achieving positive outcomes for the youth in their care.

In light of these problems, Disability Rights Ohio recommends that the state take the following steps to assess and improve the services that are provided to these youth.

Use Data Effectively

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Use available data to assess services and improve outcomes for youth and families

- Dedicate staff to analyze data and develop a quality improvement program

- Make data available to the public

There is a wealth of information about children in RTFs and the services they receive— demographics, lengths of stays, incidents such as restraint and seclusion, education and testing outcomes, Medicaid other insurance billing, readmission rates—yet the state is not gathering or using this data to monitor or improve this system. Ohio must harness the data that is available to assess the services being provided to these youth and take steps to improve their outcomes. Ohio should insist on investing its resources in services that lead to positive outcomes for youth.

One notable example is the semi-annual reports that RTFs provide to OhioMHAS about restraint and seclusion. For several years, OhioMHAS has promoted the reduction of restraint and seclusion by all mental health providers, so the state could use the facility reports to track trends and identify facilities that are achieving these goals or that need technical assistance from the department. Yet the department has not released any reports on the number of restraint and seclusion incidents in RTFs since 2012, and this report only covered a small portion of the population.37 OhioMHAS has not produced any benchmarks or goals in an effort to reduce the use of restraint and seclusion, and has not required the RTFs to implement outcome-based strategies for reducing restraint and seclusion.

There is a clear desire from stakeholders to not only have the state examine data and produce reports, but to also assist in development of goals and benchmarks. Ohio should dedicate a qualified staff person to collect and analyze data and assist in the development and execution of a quality improvement program for RTFs. This staffperson should work with stakeholders--including youth, families, and providers--to develop a system of data collection, assessment, and response.

The data and analysis should be publicly available so youth, families, providers, legislators, and other stakeholders can make informed decisions about how to improve the system of residential care. Similar efforts have been accomplished by the long-term care industry and the Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities, which have online tools for reviewing information about facilities’ compliance with regulations.

Prevent Unnecessary Institutionalization by Prioritizing High-Quality Community-Based Services

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Make a statewide, cross-agency commitment to eliminate unnecessary residential placements

- Incentivize diversion from residential placements through development of high-quality community-based services

- Perform a statewide needs assessment and develop a level of care tool for RTF admissions

- Ensure that community-based services are funded appropriately and available throughout the state

Despite the consensus that youth should receive services in their own homes and communities, many youth end up in RTFs because of the lack of high-quality community-based services. Ohio can change this situation by committing to eliminating unnecessary institutionalization and developing robust community-based services. By diverting youth from unnecessary RTF placements, the state would be making RTF services more available for those youth who actually need them for short-term out-of-home stabilization.

Youth who need mental health services have a right to receive those services in home and community-based settings instead of facilities. In the landmark Olmstead case, the U.S. Supreme Court interpreted the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) to require states to discontinue practices that unduly segregate people with disabilities in institutions instead of providing services in integrated, community-based settings.38 The U.S. Department of Justice has found the state of West Virginia in violation of the ADA for unnecessarily institutionalizing children in settings that are similar to Ohio’s RTFs.39

Ohio has successfully addressed unnecessary institutionalization in other settings through a strategy that could be implemented for youth who need mental health services. In 1994, the Ohio Department of Youth Services (ODYS) launched RECLAIM Ohio, which provided a financial incentive for juvenile courts to divert youth from state-operated juvenile correctional facilities. In 2009, the department implemented a new iteration of the program, Targeted RECLAIM, which provided additional assistance for the counties that historically committed the highest numbers of youth to the state facilities. The RECLAIM programs have resulted in a significant reduction in commitments to ODYS: the average population has dropped from over 2,600 youth in 1992 to 470 in 2015.

Ohio could make a similar impact on unnecessary institutionalization in RTFs by making a statewide commitment to providing high-quality community-based services as an alternative to residential treatment when appropriate to the child’s needs. All state and local agencies involved in funding or coordinating residential placements for children should adopt a “community first” approach, and the state should fund incentive programs for the development of high-quality community-based services that would divert youth from unnecessary RTF placements.

To assist in the development of community-based alternatives and to ensure that youth are not unnecessarily placed in RTFs, Ohio should perform a statewide needs assessment and develop a level of care tool for admission to RTFs. Stakeholders have noted that RTF providers are being asked to provide services to all youth despite their wide-ranging individualized needs—which can include juvenile justice involvement, extensive trauma histories, autism, or other developmental disabilities—because Ohio has so few specialized programs to meet these needs. A statewide needs assessment will assist Ohio in identifying which specific services are needed, and ensure that there are enough providers, both community and residential. Similarly, a level of care tool would standardize decisions across the many agencies that are involved in RTF placements.

Some efforts to build community-based services are underway through Ohio’s behavioral health redesign process. To ensure that those services meet the needs of youth and reduce the unnecessary use of residential treatment, the state must set rates for these services that are high enough to incentivize providers to offer these services in all areas of the state and must establish procedures for monitoring the quality and fidelity of the services.

Improve Quality of Residential Treatment

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Unify state standards and oversight

- Develop a rating system to incentivize and reimburse the adoption of outcome-based practices, including:

- Implementation of trauma-informed care

- Elimination of restraint and seclusion, including chemical restraint

- Engagement of families and youth, including elimination of custody relinquishment

- Prioritization of discharge planning and community connection

- Ensure health, safety, and rights of youth in residential treatment

- Prevent abuse and neglect through empowerment and mandated reporting

- Establish a statewide ombudsman office for children

Placement in a RTF should be carefully considered when there are no other options for home or community based treatment. RTF services should be provided in a manner that aligns with best practice, is outcome driven, and protects youth from abuse and neglect. While the current regulations provide a minimum standard for health and safety, they do not ensure that facilities are in line with best practices that lead to sustained positive outcomes.

Unify State Standards and Oversight

One significant barrier to improving quality of residential treatment is the lack of a single state agency to oversee these facilities. Some RTFs are licensed only by OhioMHAS, some are licensed only by ODJFS, and some are licensed by both agencies. Providers report frustration because the state agencies’ rules can be inconsistent or interpreted in different ways by the state surveyors, including important health and safety protections and regulations about restraint and seclusion. In addition, unlike ODJFS, OhioMHAS surveyors are not assigned solely to RTFs—they also oversee hospitals, adult care facilities, and behavioral health agencies—so they are unable to devote sufficient time and attention to overseeing these facilities. To address this barrier and provide leadership for improving quality of RTFs, the state should establish a unified cross-agency team to license and oversee these facilities. This cross-agency team should include the Ohio Department of Education, to oversee the educational services provided to youth in RTFs. As a first step, ODJFS and OhioMHAS should unify their regulation and enforcement of restraint and seclusion.

Incentivize Evidence-Based Practices

With unified oversight, Ohio could implement a quality-improvement system for RTFs that goes beyond minimal licensing requirements. The state has modeled such systems in other areas, including the Step Up to Quality40 program for early childhood education and care programs and quality incentive payments for nursing homes. In the Step Up to Quality program, all publicly funded childcare providers and preschools are assessed for compliance with evidence-based standards for early childhood education, and are assigned one to five stars; private providers also may choose to participate. Unlike the state’s “pay for performance” health care models, Step Up to Quality measures do not affect a provider’s reimbursement rates. However, parents can use the publiclyavailable information to choose the best program for their children.

Although RTFs are different from early childhood programs because of the varied needs of the youth that are being served, it is possible to develop standardized, understandable information about the programming offered by each RTFs, how this programming aligns with best practices, and what outcomes are anticipated. This information could include what evidence-based or best practice programming is offered, what behavior management strategies are utilized, and what types of training staff have received.

There is a wealth of information available about the evidence-based practices that RTFs should implement. Due to workforce barriers and funding restrictions, providers have difficulty implementing these practices. As part of the quality improvement system, Ohio should incentivize adoption of these practices by reimbursing out-of-pocket expenses for providers who adopt these practices. However, Ohio should be cautious about implementing a quality improvement system that leads providers to refuse to serve youth with complex needs out of fear that they will fail to meet the rating benchmarks.

Trauma-Informed Care

Implementation of trauma-informed care at RTFs would have beneficial ripple effects in all aspects of residential treatment. Most of the youth in RTFs have histories of trauma, and many have experienced multiple forms of trauma in their lifetimes.41 Researchers estimate that rates of trauma exposure for youth at RTFs ranges from 50% to over 70%.42 Over 90% of traumatized youth in RTFs have been exposed to multiple forms of trauma.43 These youth require care that is informed by this trauma and helps them develop the skills and tools needed to achieve positive outcomes.44 Other states have adopted this approach, and national curricula are available for facilities and systems to implement TIC.

While OhioMHAS has made great progress in developing trauma informed systems of care by providing training, developing an education campaign, hosting summits, and forming six regional collaboratives,45 there are barriers to full implementation at the treatment level. There is no monitoring or oversight to ensure that staff are appropriately trained and are implementing the trauma informed care practices with fidelity. As a result, facilities continue to maintain policies and physical environments that do not allow for choices, sense of calm, comfort, or access to outdoor spaces and safety.

Elimination of Restraint and Seclusion

In order to truly implement trauma-informed care, Ohio must continue its work to eliminate restraint and seclusion, including chemical restraint. Research has demonstrated that these practices re-traumatize youth and prevent positive outcomes.46 While there are regulations in place that limit the use of restraint and seclusion,47 there is no systemic effort to reduce these harmful interventions in RTFs. In June 2015, OhioMHAS and DODD held a state forum on Trauma Informed Care that included discussion on restraint and seclusion.48 At the forum, participants identified strategies for agencies to implement alternatives to seclusion and restraint. Yet neither department has publicly revealed any efforts to implement such strategies.

Family and Youth Engagement

Families and youth are more successful in the short and long term when care is family-driven and youth are involved in their treatment.49, 50 However, funding structures and facility practices instead have the effect of alienating children from their families. Ohio has an effective family advocacy program, the Parent Advocacy Connection administered by the National Alliance on Mental Illness of Ohio, but it is only available in about half of Ohio’s counties, for families who are involved in service coordination through the Family and Children First Council. The program has been flat funded for ten years.

Ohio’s first priority in this area must be to eliminate custody relinquishment for the purpose of receiving mental health or other necessary services. When families are forced to relinquish custody to pay for residential treatment, they are prevented from having full involvement in their child’s care, which is managed by a children services case worker. Ohio’s Joint Legislative Task Force on Multi-System Youth has recommended re-establishing state funding for services to reduce the need for custody relinquishment.

Facilities also need to implement practices that involve youth and families in their services. Residential facilities often operate on normal business hours, when it is difficult for family members to visit or be involved in treatment, especially when youth are placed far from their homes. Treatment programs are typically designed around the schedule that works for the staff, not the family. In addition, programs often limit youth home visits or require youth to “earn” the ability to visit family, further reducing family involvement.

Our review of RTFs found no residential program that involves youth in the training, development, or evaluation of RTF staff. Only a limited number of facilities were able to confirm youth were involved in program workgroups or committees. In addition, facilities continue to use treatment programs which utilize ‘levels’ or ‘points’ for youth based on behavior. This practice is not evidence-based and does not lead to positive outcomes for youth and, for some youth, increases use of restraint or seclusion.51

Additionally, cultural competency practices have been widely developed and adopted in the mental health field, and research demonstrates that these practices can improve outcomes in mental health treatment.52, 53 However, there are no requirements for RTF staff to engage in ongoing cultural competency training or to perform cultural competency assessments. While the regulations do contain language prohibiting discrimination, there are no requirements for care to be delivered based on best practices in cultural competency.54

Discharge Planning and Community Connection

Facilities need to begin discharge planning at the time of admission, with the active involvement of youth and their families. Stays at RTFs are to be brief with a goal of transitioning youth safely back to their homes and communities as soon as possible.55 Length of stay in RTFs should not be any longer than what is therapeutically necessary for the youth. Youth have the most positive outcomes when discharge planning begins on admission56 and treatment consistently focuses on building skills for success in the community.57 These plans must also address the needs of the family, to ensure that the youth and family are equipped to function successfully when the youth returns home. For youth involved with children services, their case workers should also take an active role in discharge planning early in the process.

Treatment plans and facility practices also need to foster community connections to the services youth receive prior to, during, and after residential treatment. In addition to being separated from their families when they enter RTFs, youth are also separated from their communities and opportunities to participate in education and employment. Facilities should ensure that youth are connected to education services (including applying for post-secondary options), employment services, and other community-based services that can assist them with transitioning back into their communities and into adulthood.

Ensure Health, Safety, and Rights

To protect youth in RTFs from abuse, youth must understand their rights and all incidents of abuse must be reported. Current rules require that facilities notify youth about their rights, but often those notifications are not tailored to the age or learning abilities of the youth. Rights notifications should be updated to be developmentally appropriate and in a language they understand. Youth should receive frequent reminders about how to report abuse.

Ohio also needs to close the gap in its mandated reporter statute. All RTF staff should be mandated reporters and should receive annual training about their duty to report.

To track incidents of alleged abuse or neglect and to ensure compliance with state policies on restraint and seclusion, facilities should be required to provide more detailed information in incident reports. These reports should describe the antecedents to the incident, the actions of all involved individuals, and photographs of any youth injuries.

The rights of youth in Ohio would be best protected through a dedicated ombudsman office for their rights. In 2014, the National Conference of State Legislatures noted that Ohio is in the minority of states that does not have a statewide ombudsman for children in out-of-home care.58 County children service offices operate ombudsman offices, but there is no state oversight and their operations are not standardized. Children in residential settings would benefit from a statewide advocate or ombudsman to review complaints and assist in resolving concerns, similar to the Long-Term Care Ombudsman for adults.

SIDENOTE

In March 2015, an employee of a Residential Treatment Facility in Northern Ohio was charged with over 70 incidents of abuse that occurred during his six year employment at the facility.

(Source: Bucyrus Telegraph, March 26, 2015)

Conclusion

Ohio has the opportunity to assess and improve its mental health service system, and especially its residential facility system, in ways that will have a substantial positive impact on the youth who need these services. We encourage the state to make the most of this opportunity by using models within the state to achieve the desired outcomes of addressing the needs of these youth and preparing them for a successful transition into adulthood.

Acknowledgements

Disability Rights Ohio appreciates the work of Dr. Janice LeBel and Beth Caldwell, who conducted an exhaustive review of Ohio’s residential treatment system and lent their expertise from years of experience with systems in Massachusetts, New York, and other states. Their insights and recommendations formed the basis for this report and provided an invaluable framework for this review.

Disability Rights Ohio acknowledges the youth who inspired and informed this report, including Faith Finley, Kenneth Barkley, and the many youth who have spoken to Disability Rights Ohio throughout our work in these facilities.

Disability Rights Ohio also appreciates the many stakeholders who provided information for our review of this system and the development of this report, including Danielle Gray, Laura Austen, Katie Dillon, Tracey Field, Chad Hibbs, Joyce Callard, Monica Kress, Kim Kehl, David Lucey, Barbara Manuel, Mark Mecum, Janel Pequignot, Marianne Riley, Jane Robertson, Angela Schoepflin, Steve Stone, Debra Rex, Linda Schettler, Lisa Leskovec, Kathleen Sabol, Louis Wainwright, James McCafferty, Robin Saldivar, Deb Mehl, Richard Frank, Dr. Ben Kearney, Donna Keegan, Joan Sila, Kia Brown, Angela Nikkel, Eric Cummins, Toyetta Barnard-Kirk, Louanne O’Neal, Kristy Blazer deVries, Maureen Corcoran, Judy Jackson-Winston, Betsy Johnson, Ryan Gies, Erin Davies, Dr. Jacqueline Wynn, Kelly Smith, Bruce Tessena, Vera Brewer, Ebony Speakes-Hall, Heather Distin, Ellen Harvey, Gary Daniels, Kay Spergel, and other youth, family members, and professionals. Disability Rights Ohio received information for this report from the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, Ohio Department of Medicaid, Ohio Department of Youth Services, Ohio Governor’s Office of Health Transformation, Ohio Family and Children First Council, Office of the Ohio Public Defender, Ohio Juvenile Justice Coalition, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Lorain County, Mental Health and Addiction Advocacy Coalition, Public Children Services Association of Ohio, Ohio Association of Child Caring Agencies, National Alliance on Mental Illness of Ohio, ADAMHS Board of Cuyahoga County, and Mental Health and Recovery Board of Ashland County.

This publication was made possible by funding support from SAMHSA. These contents are solely the responsibility of Disability Rights Ohio and do not necessarily represent the official views of SAMHSA.

Endnotes

1 Disability Rights Ohio was established in 2012 as a non-profit corporation and designated as Ohio’s protection and advocacy system as of October 1, 2012. DRO’s predecessor, Ohio Legal Rights Service, conducted numerous investigations of residential facilities for youth and advocated for youth in these settings. Disability Rights Ohio has continued this advocacy.

2 Dr. Janice LeBel is a licensed, Board-Certified Psychologist with more than thirty years’ experience in the public sector working primarily in mental health but also with child welfare, juvenile justice, and intellectual and developmental disability populations. She is the Director of Systems Transformation at the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health (DMH) and oversees a statewide system of inpatient, secure residential and community-based care for children and adolescents. Dr. LeBel also leasds the nationally-recognized DMHRestraint/Seclusion (R/S) Precention Initiative and an interagency initiative with the same focus involving child-serving state agencies and the public and private special education schools in the state. She is a founding member of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors’ Office of Technical Assistance Center’s teach faculty, co-authored an evidence-based curriculum on R/S Prevention, and works to implement trauma-informed care and R/S prevention efforts throughout the United States and internationally. Dr. LeBel has provided expert testimony at Congressional Briefings and legal proceedings. She has researched and published on seclusion and restraint-related issues and presented at many national and international forums. Dr. LeBel also serves as a peer reviewer for several journals.

Beth Caldwell, M.S., is the principal consultant in a consulting group dedicated and committed to supporting individuals with special needs and organizations who serve these individuals in achieving their missions, and fully implementing their values, so that each individual, child, and family served can realize his/her full potential. Well versed in the literature on effectiveness in the fields of mental health, substance abuse, child welfare, juvenile justice, and education, and utilizing state-of-the-art training and consultation practices, Ms. Caldwell has been called upon frequently to provide technical assistance and to develop written documents relating to issues in the field. She is the director of the national Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), an initiative dedicated to moving children’s residential programs, and their community counterparts, to the best practice arena. She also has served as a faculty member for the National Center for Trauma Informed Care (formerly the Office of Technical Assistance), National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; as an individual consultant and faculty member, she has provided training, consultation, and/or on-site reviews for staff and programs in all 50 states and several countries since 2001 on BBI best practices, trauma informed care, resiliency and recovery, family-driven and youth-guided care, and preventing the need for coercive interventions, including restraint and seclusion.

3 Mercer Government Human Services Consulting. (2008). White Paper Community Alternatives to Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facility Services Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Office of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services

4 Ohio Association of Child Caring Agencies, “Residential Centers and Group Homes” http://www.oacca.org/find-a-service/substitute-care-out-of-home-care/residential-treatment/ Accessed 6/8/2016

5 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1999. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Author. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/chapter3/sec7.html#treatment

6 American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry “Principles of Care for Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Mental Illness in Residential Treatment Centers” June 2010. https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/clinical_practice_center/principles_of_care_for_children_in_residential_treatment_centers.pdf

7 Monroe, Kristine, Program Administrator, Ohio Department of Job and Family Services “Congregate Care in Ohio” Presentation for workgroup session during the Ohio Association of Child Caring Agencies Annual Conference, September 9, 2016

8 Singer, Mark “Assessment of Violence Exposure Among Residential Children and Adolescents” Residential Treatment for Children and Youth 2007, 24 (1/2) 159-174

9 Zelechoski, et al “Traumatized Youth in Residential Treatment Settings: Prevalence, Clinical Presentation, Treatment and Policy Implications” Journal of Family Violence 2013. 28: 639-652

10 Ohio Administrative Code Chapter 5101:2-9 Children’s Residential Centers, Group Homes and Residential Parenting Facilities

11 Ohio Administrative Code Chapter 5122-30 Licensing of Residential Facilitie

12 Barth, R. P. (2002). Institutions vs. foster homes: The empirical base for a century of action. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, School of Social Work, Jordan Institute for families http://www.crin.org/en/docs/Barth.pdf

13 Barth, R. P., Greeson, J. K., Guo, S., Green, R. L., Hurley, S., Sisson, J. (2007). Outcomes for youth receiving intensive in-home therapy or residential care: A comparison using propensity scores. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77 (4) 497-505

14 Hoagwood, K., Burns, B., Kiser, L., Ringeisen, H. & Schoenwald, S. K. (2001). Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services. Psychiatric Services, 52 (9), 1179-1189.

15 Alexander, J., Pugh, C., Parsons, B., & Sexton, T. (2000). Functional Family Therapy. In D. S. Elliott (Ed.), Blueprints for Violence Prevention (Vol. 3). Boulder, CO: Venture Publishing.

16 Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services “Initial Overview of Service Map for Multi-System Youth Issues” 2015.

17 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1999. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Author. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/chapter3/sec7.html#treatment

18 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1999. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Author. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/chapter3/sec7.html#treatment and Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law “Fact Sheet: Children in Residential Treatment Centers” http://www.bazelon.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=D5NL7igV_CA%3D&tabid=247

19 Conner, DF et al “Characteristics of Children and Adolescents Admitted to a Residential Treatment Center” Journal of Child and Family Studies 13(4). 2004. 497-510.

20 Ohio Department of Mental Health, Strong Families, Safe Communities, Analysis of State Fiscal Year 2014 Program Activities. March 31, 2015 http://mha.ohio.gov/Default.aspx?tabid=439

21 Ohio Family and Children First SFY15 FCSS Annual Report Summary January 2016

22 Ohio Administrative Code Chapter 5101:2-9 Children’s Residential Centers, Group Homes, and Residential Parenting Facilities http://codes.ohio.gov/oac/5101%3A2-9

23 Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law “Keeping Families Together: Preventing Custody Relinquishment for Access to Children’s Mental Health Services” http://www.bazelon.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=7yUM_jdexco%3d&tabid=230

24 Public Children Services Association of Ohio “Addressing the Needs of Ohio’s Multi-System Youth” 2016 http://www.pcsao.org/pdf/advocacy/MultiSystemYouthBriefPCSAO.pdf

25 Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law: Fact Sheet: Children in Residential Treatment Centers http://www.bazelon.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=D5NL7igV_CA%3D&tabid=247

26 “Faith Finley died after being restrained in controversial position,” The Plain Dealer, http://blog.cleveland.com/metro/2009/01/faith_finley_died_after_being.html

27 “Death of teen who was physically restrained at Berea group home ruled homicide,” The Plain Dealer, http://www.cleveland.com/berea/index.ssf/2014/05/death_of_teen_physically_restr.html

28 “Former Parmadale employee pleads guilty to illegal sexual encounters with two teenage girls from the center,” The Plain Dealer, http://www.cleveland.com/court-justice/index.ssf/2014/06/former_parmadale_employee_plea.html

29 Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Seclusion and Restraint Six Month Data Report Results Residential Facility (Type 1) January through June 2012 http://mha.ohio.gov/Portals/0/assets/Regulation/LicensureAndCertification/Seclusion-and-Restraint-Type%201-Residential-January-through-June-2012-Report_11-13-2013_FINAL.pdf

30 Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law “Fact Sheet: Children in Residential Treatment Centers” http://www.bazelon.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=D5NL7igV_CA%3D&tabid=247

31 U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Re: United States’ Investigation of the West Virginia Children’s Mental Health System Pursuant to the Americans with Disabilities Act June 1, 2015 https://www.ada.gov/olmstead/documents/west_va_findings_ltr.pdf

32 Dishion T.J. McCord J. & Poulin F. (1999) When interventions harm. Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 54, 755-764

33 Brown, E.C. & Greenbaum, P.E., Reinstitutionalization After Discharge from Residential Mental Health Facilities: Competing Risks Survival Analysis As cited in Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law: Fact Sheet: Children in Residential Treatment Centers http://www.bazelon.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=D5NL7igV_CA%3D&tabid=247

34 Bettmann, et al. “Who are they? A descriptive study of adolescents in wilderness and residential programs” Residential Treatment for Children & Youth. 2011 28, 192-210.

35 Ohio Rev. Code 2151.421

36 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1999. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Author. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/chapter3/sec7.html#treatment

37 Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Seclusion and Restraint Six Month Data Report Results Residential Facility (Type 1) January through June 2012 http://mha.ohio.gov/Portals/0/assets/Regulation/LicensureAndCertification/Seclusion-and-Restraint-Type%201-Residential-January-through-June-2012-Report_11-13-2013_FINAL.pdf

38 Olmstead v. L.C., 527 U.S. 581 (1999).

39 Letter from Vanita Gupta to Governor Earl Ray Tomblin, June 1, 2015, available at https://www.ada.gov/olmstead/documents/west_va_findings_ltr.pdf.

40 http://jfs.ohio.gov/cdc/stepUpQuality.stm

41 Bettmann, et al. “Who are they? A descriptive study of adolescents in wilderness and residential programs” Residential Treatment for Children & Youth. 2011 28, 192-210.

42 Jaycox, et al, “Trauma exposure and retention in adolescent substance abuse treatment” Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004. 17. 113-121. Warner and Pottick, “Latest Findings in Children’s Mental Health: Policy Report” Annie E. Casey Foundation. 2003. 2, 1-2

43 Briggs et al, “Trauma Exposure, psychological functioning and treatment needs of youth in residential care: preliminary findings from the NCTSN Core Data Set” Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma. 2012 5, 1-15.

44 Kessler, John M. “A Call for the Integration of Trauma-Informed Care Among Intellectual and Developmental Disability Organizations.” Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 2014: 34-42

45 Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services and Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities Creating Environments of Resiliency and Hope in Ohio: Trauma Informed Care (TIC) Statewide Initiative Progress to Date December 2015 http://mha.ohio.gov/Default.aspx?tabid=104

46 Fisher, William A. “Restraint and Seclusion: A Review of the Literature.” American Journal of Psychiatry, 1994: 1584-1591.

47 Ohio Administrative Code Chapter 5101:2-9 Children’s Residential Centers, Group Homes, and Residential Parenting Facilities http://codes.ohio.gov/oac/5101%3A2-9

48 http://www.oacca.org/alternatives-to-seclusion-and-restraint-forum/

49 Frensch, Karen and Gary Cameron “Treatment of Choice or a Last Resort? A Review of Residential Mental Health Placements for Children and Youth” Child and Youth Care Forum 2002. 31(5) 307-339

50 Spencer, Sandra et al “Family Driven Care in America: More Than a Good Idea” Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2010 Aug; 19(3): 176–18

51 Mohr, Wanda et al “Beyond Points and Level Systems: Moving Toward Child-Centered Programming” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 2009 79(1) 8-18

52 Stanely, Sue et al “The Case for Cultural Competency in Psychotherapeutic Interventions” Annual Review of Psychology 2009, 60, 525-548

53 Giner, D and TB Smith “Culturally adapted mental health intervention: A meta-analytic review.” Psychotherapy 2006 Winter: 43(4) 531-548

54 Ohio Administrative Code Chapter 5101:2-9 Children’s Residential Centers, Group Homes, and Residential Parenting Facilities http://codes.ohio.gov/oac/5101%3A2-9

55 James, S., “What Works in Group Care?—A Structured Review of Treatment Models for Group Homes and Residential Care.” Children and Youth Services Review, 33:308-321 (2011)

56 Magellan Health Services “Perspectives on Residential and Community-Based Treatment for Youth and Families” 2008. http://www.mtfc.com/2008%20Magellan%20RTC%20White%20Paper.pdf

57 James, S., “What Works in Group Care?—A Structured Review of Treatment Models for Group Homes and Residential Care.” Children and Youth Services Review, 33:308-321 (2011)

58 http://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/childrens-ombudsman-offices.aspx